As we gazed across the open field, we spotted a large, black critter slowly moving along a patch of tall weeds. Using our binoculars, we identified the “dark blob” as an adult Black Bear munching on some type of root it had pulled out of the moist soil. We were parked along the Wildlife Drive in Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) and before we departed for the evening, we were lucky enough to spot 5 more adults and 2 cubs. The last adult we watched sat lazily in a field of sweet potatoes just as the sun was setting. I would like to say it was doing something spectacular, but it just sat there, like it was finishing the last bite at an all-you-can eat buffet, then got up and proceeded to take a nice long poop, before strolling away. I didn’t think it wanted its picture taken at that moment, so I just put the camera away. Tyler and I looked at each other, laughed, and hurriedly jumped back in the car to escape the attacking mosquitos. Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge has what is believed to be one of the largest concentrations of Black Bear found in the southeastern United States. This refuge, along with stops at Pocosin Lakes NWR, Pea Island NWR and Cape Hatteras National Seashore, were part of a quick weekend adventure Tyler and I took to the Outer Banks/Inner Banks area of Eastern North Carolina.

INNER BANKS

Top Right-Bald Eagle, Bottom Left- American White Water Lily, Bottom Right-Northern Red-bellied Cooter

I consider Alligator River NWR and Pocosin Lakes NWR part of the “Inner Banks” region of Eastern North Carolina-an area loosely defined as, East of I-95 and just west of the Outer Banks. Both Alligator River NWR (152,000 acres) and Pocosin Lakes NWR (110,000 acres) were established to protect and preserve a unique type of wetland habitat called a pocosin, and the wildlife associated with it. A pocosin habitat is made up of poorly drained soils which are incredibly high in organic material, like peat. Because of this, in wet rainy weather, these deep peat deposits can retain large quantities of water. In dry conditions, the area is very susceptible to wildfire and can literally slowly burn for months. The vegetation can be very thick, with a variety of shrubs, and trees such as Bald Cypress, Black Gum and Loblolly Pine.  The word pocosin comes from a Native American term which roughly translates to “swamp-on-a-hill.” The main wildlife attractions at Alligator River NWR are Black Bears, American Alligators and the rare Red Wolf. Unfortunately, we didn’t catch sight of any Alligators, even after taking a 3-hour kayak trip deep into the backwaters of the refuge. Alligator River NWR is at the limit of their northern range, so they’re not as common here as they would be further south. However, we did see many other species of wildlife including Bald Eagles, Red-headed Woodpeckers, Turtles and Deer (and the previously mentioned Black Bears). But our real quest was to learn more about the federally endangered Red Wolf……and maybe even hear or see one.

The word pocosin comes from a Native American term which roughly translates to “swamp-on-a-hill.” The main wildlife attractions at Alligator River NWR are Black Bears, American Alligators and the rare Red Wolf. Unfortunately, we didn’t catch sight of any Alligators, even after taking a 3-hour kayak trip deep into the backwaters of the refuge. Alligator River NWR is at the limit of their northern range, so they’re not as common here as they would be further south. However, we did see many other species of wildlife including Bald Eagles, Red-headed Woodpeckers, Turtles and Deer (and the previously mentioned Black Bears). But our real quest was to learn more about the federally endangered Red Wolf……and maybe even hear or see one.

MY RED WOLF SOAP BOX

Red Wolves are one of the most endangered species in the world. Currently, the only wild population is limited to a five county area of Eastern North Carolina, and Alligator River NWR has been the focus of a restoration recovery effort to reintroduce the endangered Red Wolf into the wild.

In 1973, Red Wolves were declared an endangered species. Efforts were initiated to locate and capture the remaining wild wolves found in the Louisiana and Texas coast area. Of the 17 remaining wolves captured by biologists, 14 became the founders of a successful captive breeding program. The founding Red Wolves had to be a pure bred species, meaning not a mixed breed of wolf and coyote. Consequently, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service declared Red Wolves extinct in the wild in 1980. By 1987, enough Red Wolves were bred in captivity to begin a restoration program on Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. Since then, the program has expanded to include three national wildlife refuges, a Department of Defense bombing range, state-owned lands, and private property, spanning a total of 1.7 million acres. But the program hasn’t been without conflict and controversy, and management of the wolves is now changing, and in my opinion, is not good news for the future of Red Wolves. After initially increasing, the population plateaued and then declined. Today, only approximately 35 wild wolves remain, with a further 200-plus wolves in captive breeding facilities. The program is referred to as “the non-essential, experimental population of Red Wolves in North Carolina (NEP).” Many people feel the reintroduction has been a failure-claiming it’s been too expensive and has decreased deer populations. Still others question whether the animals are truly pure bred wolves at all. Currently, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is proposing a rule that would “restrict management to the Alligator River NWR and the Bombing Range.” In addition, “under this new proposal, there would be no prohibitions on the take of red wolves on non-federal lands outside the NEP area, provided the take occurs in conjunction with an otherwise lawful activity.” In other words, their recovery range will be drastically reduced from 1.7 million acres to approximately 198,000 acres, and it would be legal to kill any Red Wolves that wander outside these two areas on to private property.

Although we learned a lot about this controversial animal, and the reintroduction program, unfortunately, Tyler and I didn’t get the opportunity to hear, or see, any Red Wolves on our trip into Alligator River NWR. However, I’m planning on returning soon to learn more about the decisions being made to change the management of the Red Wolves, and possibly get a chance to hear or see this beautiful animal nicknamed the “the ghost wolf!”

OUTER BANKS

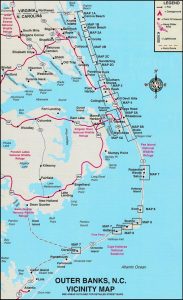

As part of our trip, Tyler and I wanted to spend some time near the ocean, so we headed east to the Outer Banks to possibly catch some early migrating shorebirds. This 200-mile stretch of barrier islands is located just off the east coast of North Carolina and southeast Virginia. It includes the islands of Bodie, Roanoke, Hatteras and Ocracoke. These islands separate the Atlantic Ocean from several large Sounds (Albermarle, Currituck, Pamlico). It’s a major tourist destination because of the miles of beautiful beaches and water-based recreation, rich history and diverse amount of wildlife. Even with the increasing amount of human development, the Outer Banks has a rugged, raw beauty to it, constantly battling Mother Nature with harsh weather, rough waves and shifting sand dunes. It’s easy to see why so many people enjoy visiting here, and, the reason that so many people are deciding to relocate to the area permanently. Like so many of our other amazing, natural places, I just hope it doesn’t get “loved to death!”

As part of our trip, Tyler and I wanted to spend some time near the ocean, so we headed east to the Outer Banks to possibly catch some early migrating shorebirds. This 200-mile stretch of barrier islands is located just off the east coast of North Carolina and southeast Virginia. It includes the islands of Bodie, Roanoke, Hatteras and Ocracoke. These islands separate the Atlantic Ocean from several large Sounds (Albermarle, Currituck, Pamlico). It’s a major tourist destination because of the miles of beautiful beaches and water-based recreation, rich history and diverse amount of wildlife. Even with the increasing amount of human development, the Outer Banks has a rugged, raw beauty to it, constantly battling Mother Nature with harsh weather, rough waves and shifting sand dunes. It’s easy to see why so many people enjoy visiting here, and, the reason that so many people are deciding to relocate to the area permanently. Like so many of our other amazing, natural places, I just hope it doesn’t get “loved to death!”

Most of our day on the Outer Banks was spent visiting Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Pea Island NWR, where we enjoyed seeing a few shorebirds such as Sanderlings, Willets, American Oystercatchers, Ruddy Turnstone, Terns, Brown Pelicans, Black-bellied Plovers, Black Skimmers, and one of my favorites, Whimbrel. Pea Island NWR is 13 miles long and about 5,834 acres. It was established in 1938 to provide nesting, resting, and wintering habitat for migratory birds, as well as protection of habitat for the endangered Loggerhead Sea Turtle. The refuge also provides environmental education and interpretation for thousands of visitors annually.

Above-Ruddy Turnstone (L) and Willet (R) and nesting Least Terns and Black Skimmers (bottom)

Along with checking out the variety of birds, we also managed to get in a little exercise by climbing up the 257 steps to the top of the famous Cape Hatteras Light Station, the tallest lighthouse in the U.S. at 208 feet. As we ascended the iconic black and white striped structure, I realized I no longer get embarrassed as I stopped to take my 7th break on the steep, winding staircase, and several chattering 10-year olds who barely seem to be breathing hard, shuffled on by me! One of them paused to politely ask me, “Hey mister, are you ok?” As I lifted my head to see what kind of creature would be asking me this 200’ straight up, I muttered back, “Why, don’t I look ok?” “No, not really,” the little rug rat replied, as he hunched his shoulders and trotted out of sight above me. After finally reaching the top and enjoying the awesome views, I gracefully walked past the same little tot, smiled and said, “Remember me?” The last I saw of him we were back on the ground and he was pointing at me while talking to his father. Little bugger!

Eastern North Carolina has so much to see and do with its renowned Outer Banks, and many wildlife refuges and parks of the Inner Banks. You could easily spend several weeks exploring all the region has to offer. Theresa and I will be back in a few weeks to explore the northern reaches of this area-stay tuned for Part 2 of the Outer Banks!