Winter is upon us. The invasion from the north has begun! Hundreds of them have been quietly moving south from across the boreal forests of Canada and points beyond. They’re decked out in impressive colors of rosy reds, striking golds and bold blacks and whites. What are these invaders, and why are they here? They’re birds. Very special birds that we don’t see every year. For many birders like myself that live a bit further south, we get excited about these rare visitors because we may get the opportunity to have some of these species show up at our backyard bird feeders! These seasonal movements are called irruptions, and one species is making appearances in many areas it hasn’t visited in decades!

In the bird (and birders) world irruptions are defined as large, irregular migrations of birds from their normal range, usually the far north, to areas they’re not commonly found in, like here in Virginia. Most of these irruptions occur in the winter months, and are caused by the lack of food where they typically live. They move south in search of some of the foods they eat, like the seeds of conifers and birches, berries, and for some species, small animals! Most irruptions focus on songbirds including Pine Siskins, Purple Finches, Common Redpolls, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Evening Grosbeaks, Pine Grosbeaks, Bohemian Waxwings and Red and White-winged Crossbills. These species are forest-dwelling birds, so here in the Eastern U.S. they most likely find their way to our areas by following the Appalachian Mountain range south. They may also wander many miles away from the mountains. They’ve also been described as “nomadic” feeders, meaning they may visit your feeders one day, disappear for a few days, then suddenly show up again several days later.

Pine Siskin (above left), Purple Finch (above right), Common Redpoll (below left) and Red-breasted Nuthatch (below right), Red Crossbill (bottom)

Perhaps my favorite bird of this group is the beautiful Evening Grosbeak, a bird of my childhood. This beautiful boreal species (males have a magnificent gold, black and white plumage) gets its name from the French word “gros-bec,” meaning “big beak.” Unfortunately, Evening Grosbeak populations are in serious decline due to food availability and habitat loss. The grosbeak feeds mostly on conifer and hardwood seeds in winter, but it feeds its young insects, including the spruce-budworm. But, the spruce-budworm is considered a significant forest pest in the U.S. and Canada and aerial spraying to reduce spruce-budworm infestations may negatively impact Evening Grosbeak populations.

Male Evening Grosbeak (photo courtesy of David J. Hawke)

I remember as a kid living in NE Pennsylvania watching large, hungry flocks of Evening Grosbeaks swarm to our big feeder to gorge themselves on sunflower seeds every winter in the late 1970’s and 80’s. They could scatter the shells of the sunflower seeds faster than a bench full of Major League baseball players! My dad, mom and I would enjoy gazing out the kitchen window, only breaking our observations to bravely venture out in the cold and snow to fill the feeder every few hours. Boy could they put away the sunflower seeds! Boy do I miss those days! Not sure we’ll ever see Evening Grosbeak numbers like that again.

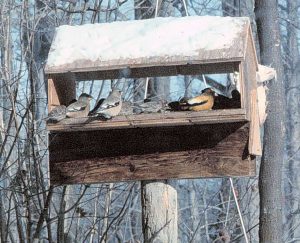

This 1980 photo shows a small flock of Evening Grosbeaks dining on sunflower seeds in our backyard feeder, in NE Pennsylvania. The gold-colored male is on the right, while the duller-colored females on the left.

This 1980 photo shows a small flock of Evening Grosbeaks dining on sunflower seeds in our backyard feeder, in NE Pennsylvania. The gold-colored male is on the right, while the duller-colored females on the left.

There are other bird species that irrupt other than the boreal forest species, such as Northern Shrike, Rough-legged Hawk and the stunning Arctic resident, the Snowy Owl. These carnivorous visitors are just as exciting to see, but they usually don’t irrupt in large numbers. Most reports are of individual birds showing up, and different than the previously mentioned birds, they’re found in open areas with scattered trees, not associated with forests.

Northern Shrike (above left), Rough-legged Hawk (above right) and a Snowy Owl sitting on a shed roof during a snow storm (below).

Before we know it, the cold winds of winter will give way to the warm breezes of spring. The bare trees will begin to bud and some of our summer resident birds will begin to return. But as long as the northern invasion continues, we’ll keep the backyard feeders filled, and maybe, just maybe, we’ll strike gold again!